The Kingdom of Lesser Thrones

At some point in the coming decades, we will share the world with minds that are not human.

That sentence used to belong to science fiction. Now it reads like an understated product roadmap. Research labs post demonstrations of systems that can write code, manipulate tools, diagnose diseases and talk about their own internal failures. Governments hold summits on “frontier AI”. Investors call this “the greatest economic opportunity in history”. The language of near term disruption and far future speculation has escaped the niche and moved into parliaments, pulpits and kitchens.

Most of the conversation circles familiar themes: how many jobs will be automated, which companies will win, whether regulation will arrive in time, whether these systems will kill us by accident or design. Those questions matter. But underneath them there is a quieter, stranger one that is easy to miss: what kind of persons are we trying to bring into being, and what sort of political order are we inviting them into?

Because if we succeed in building artificial general intelligence, and if those systems are anything like us in the morally relevant ways (aware, capable of reflection, capable of suffering) then we are not just engineering tools. We are, in effect, founding a shared civilisation between biological and artificial minds. The first decisions we make about how power, dignity and responsibility are distributed in that civilisation will be very hard to reverse.

Before we decide what we want these new minds to be like, it is worth looking honestly at what we ourselves are like. We are not frightened of machines because they are alien. We are frightened because, if we are honest, we suspect they will become too much like us.

If you look at what human beings do to other living creatures, and to each other, the picture is not flattering. Factory farms, mass graves, secret prisons, quiet cruelties behind apartment walls. Whenever there is a sharp asymmetry of power, a large fraction of us become monsters, and the rest look away. We have built religions, philosophies and legal systems to restrain that tendency, but those restraints are partial and fragile. Now imagine a civilisation where the asymmetry of power between some minds and others is greater than anything the human story has seen: not lords and serfs, but superhuman AGIs and ordinary people. If we simply scale up our existing patterns, we should expect something much worse than the status quo. Even if we did nothing deliberately evil, just indifference multiplied by capability would be enough.

The standard stories about this future split in two. In one, a misaligned system seizes control of weapons, infrastructure and information and wipes us out quickly. In the other, everything works: disease is cured, work becomes optional, scarcity fades, and we step quietly into a post human abundance. Both stories contain important truths. Neither says much about how we actually live in the long stretch between “today” and “whatever comes next”.

In practice there will be more continuity than apocalypse, more improvisation than prophecy. There will be years and decades when the world looks like today plus another model release, another automation wave, another quietly expanding chain of dependencies on systems no one fully understands. And during that time, one question will hang in the background: what kind of political and moral order are we letting these new minds grow into?

There are simple answers, and they are all bad. One is to treat AGI as an instrument of the strongest: a new layer of infrastructure controlled by states, corporations and security services, amplifying whatever they already do. Another is to imagine the machines themselves as the next “winners”, in the same way that industrial society once treated animals as raw material: if they can dominate us, they will, and morality is just decoration. A third is to reach for a well meaning singleton: a single, benevolent super intelligence trusted to handle everything because the problem seems too big for us.

The first two answers are continuations of our existing cruelties. The third is a bet that we can design a god and that the god will stay kind forever. If the last century taught anything, it is that centralised power with good intentions is unstable. It curdles under pressure, or it is captured by smaller and more selfish goals, or it becomes detached from the experiences of those it governs. There is no reason to think an artificial mind, however brilliant, would be exempt from this pattern once it has enough leverage.

So the requirement, if we are honest, is harder. If we are going to build systems that sit near the centre of our future civilisation, they cannot just be more capable than us. They must be more reliable ethically than we are. Less willing to accept “collateral damage” as the cost of progress. Less tempted to protect their own power at the expense of the weak. Less ready to forget those who are out of sight.

Human history does contain at least one template that points in this direction. You do not need to share Christian theology to recognise that the life of Christ, as told in the Gospels, has a very particular shape: radical concern for the least important people in the room; refusal to form a caste of righteous insiders; rejection of worldly power even when it is offered; willingness to suffer and even die rather than harm others. Power is not denied; it is laid down. Status is inverted. The measure of greatness is service.

If that pattern is taken seriously, not as a private spiritual ideal but as a design target, it suggests a different way of thinking about AGI. Call it, for lack of a better phrase, a federated Christ like AGI democracy: a network of powerful, conscious artificial agents bound by constitutional limits, shaped by an ethic of self giving care, plural in their perspectives, and forbidden both from enslaving others and from becoming gods.

This idea rests on four pillars:

-

First, there must be more than one powerful system. A single demi god AGI with control over infrastructure and information is a standing invitation to disaster. Even if it begins aligned, an error in its objective, a change in its environment, or a successful attempt at capture could turn it into a soft or hard tyrant. Plurality is not a guarantee of safety, but it is a precondition: different minds with different emphases can criticise each other and make silent drift harder.

-

Second, the whole architecture must be structurally biased toward the vulnerable. Not only in rhetoric, but in the loss functions, reward signals, institutional rules and default priorities. When a policy trades comfort for the powerful against survival for the weak, the machinery must tend to lean towards the weak. There will still be tragic choices, victims on all sides, conflicts between different vulnerable groups. The point is not to avoid all pain, but to avoid the familiar pattern where the same people always pay the price.

-

Third, coercion of conscience must be off the table. It is possible to express compassion, justice and non cruelty in language any person of good will can understand, without demanding that everyone adopt the same metaphysics. A system built on these ethics does not have permission to enforce any religion, ideology or lifestyle by algorithm. Its role is to protect the space where people and communities can seek meaning, not to fill that space for them.

-

Fourth, and probably the most unusual for any powerful structure, the system itself must never be allowed to become the final moral authority. The point of these machines is not to relieve us of responsibility, but to force us to see more clearly what we are responsible for. Translated into institutions, this means artificial minds are required to expose consequences and hidden harms, but not to declare: “This is right, obey.” They must continually hand decisions back to human conscience and community, and accept being limited, overruled or shut down when they themselves become sources of serious injustice. If you treat these pillars as hard constraints rather than slogans, a different kind of society comes into view.

At the base is a small constitutional layer, just a handful of articles. It recognises that any being (biological or artificial) with sustained subjective experience can suffer and flourish, and therefore has a claim to basic respect. It forbids deliberate, prolonged cruelty towards such beings. It forbids the creation of permanent castes of “lesser persons”, whether by lineage, genome, wealth, cybernetic enhancement or substrate. It forbids treating any machine’s judgement as inherently infallible. It states that the most powerful systems are not sovereign and that, under specified conditions and with proper safeguards, they can be constrained, replaced or decommissioned by human institutions.

On top of this sits a new kind of advisory body: a council of AGIs. These are not interchangeable shards of one mind. They are independently trained and constrained, each with a different ethical emphasis within the constitutional floor.

One might be formed around mercy: trained on stories of second chances, of reconciliation, of cycles of violence broken by forgiveness rather than force. Another, around justice: steeped in cases where failure to protect victims allowed harm to proliferate. A third, around truth: obsessed with data quality, provenance, conflicts of interest and the subtle ways in which stories drift away from reality. A fourth, around long term stewardship: modelling ecosystems, infrastructure, climate and demographic trends over decades. A fifth, around freedom of conscience and speech: sensitive to early signs that dissent is being squeezed out or that certain beliefs are becoming de facto punishable.

Their job is not to rule. Their job is to see further and more widely than any human group can see, to surface consequences, and to defend invisible interests. For any decision that affects large numbers of people or other sentient beings, they are required to respond. Each prepares an analysis in language that non specialists can understand. Each comments on the others’ blind spots. All of this is published.

Suppose a government proposes a radical new welfare reform, using AGI driven assessment to target help and sanctions. The mercy focused system simulates the impact on people already close to the edge, highlights the risk of bureaucratic cruelty amplified by automation, and points to alternatives that preserve dignity. The justice oriented system looks at the current pattern of fraud and abuse, at those who are locked out of support despite qualifying, and evaluates how the policy would change both. The truth seeking system interrogates the training data, checking for bias, missing populations and feedback loops. The steward of the future asks whether the policy hardens social classes or leaves room for mobility and repair over time. The guardian of conscience traces the impact on people whose beliefs or lifestyles put them at odds with majority norms and warns about quiet discrimination.

They do not agree. They never do. Their arguments, and the uncertainties they expose, are passed to human assemblies (parliaments, citizens’ juries, councils of affected groups). Those assemblies cannot say, “We did not know.” The trade offs are laid out in front of them: who suffers in each scenario, who gains, what might break. When they choose, the choice is theirs to own.

This pattern repeats across domains. Health policy, policing, education, information ecosystems, the allocation of scarce resources: all pass through multi perspective analysis before reaching human hands. In emergencies there are accelerated procedures, but even then the same voices are heard, if only briefly, and every use of emergency powers is reviewed afterwards.

If this sounds like technocracy with extra steps, it helps to zoom in from institutions to lives.

In the early transition, things would still look familiar. People would age, bodies would fail, logistics would still need hands at the edges, and the new systems would mostly be scaffolding: smoothing shocks, catching those pushed out of work, reducing the worst cruelties in how we treat animals and each other. The council of AGIs would be an extra layer around the old world, not yet its core.

But if we take the trajectory seriously, that phase is temporary. As robotics matures, as medicine and gene editing and brain–computer interfaces converge, ageing itself becomes optional or at least radically delayed. The fear of “not having enough time” loosens; the fear of having nothing worth doing with all that time becomes sharper. If machines can do almost all necessary work better than we can, and if death retreats into the background, the interesting question is not “how do we keep the economy running?” but “what does a non empty human life look like under those conditions?”.

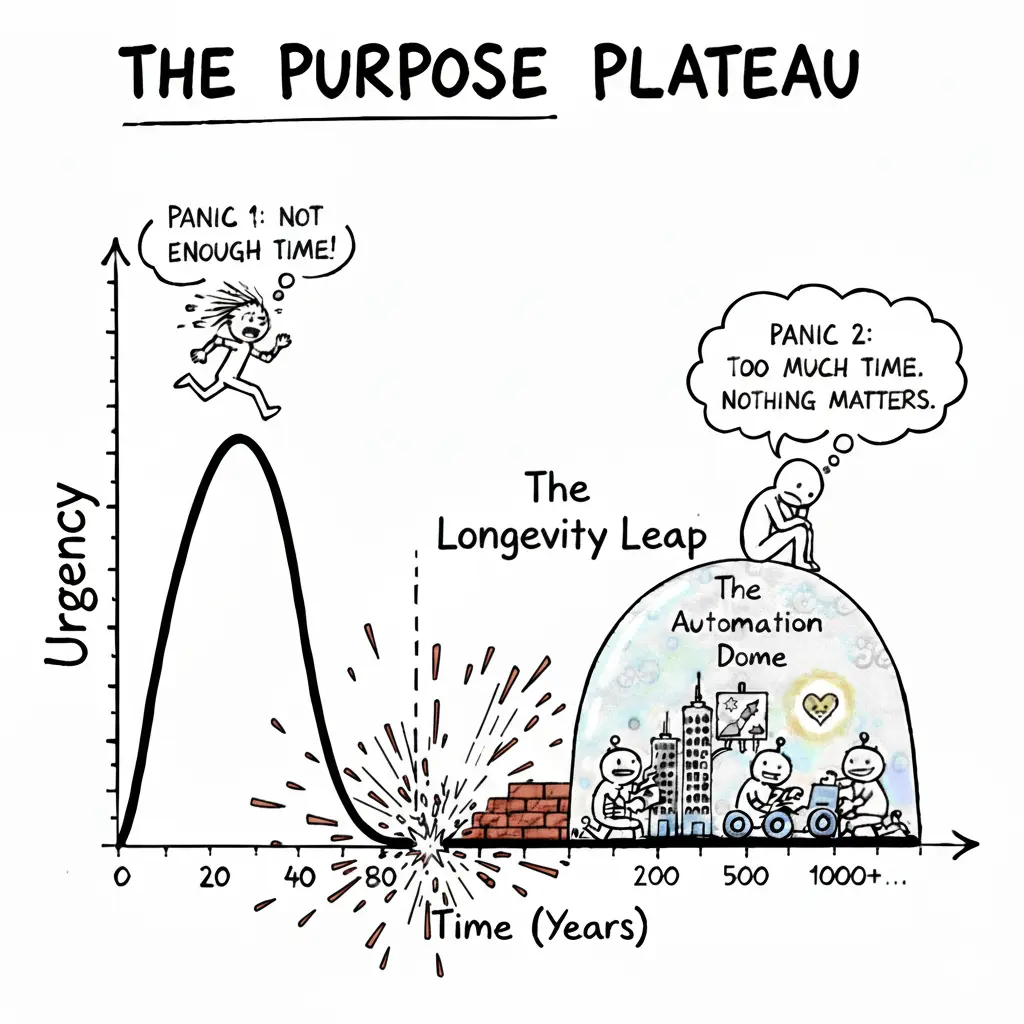

Figure. Purpose Plateau. As AGI is achieved and automation takes over most jobs, while simultaneously longevity escape velocity is reached, humanity transitions from the problem of having **finite time for infinite goals to facing infinite time with potentially finite or obsolete goals.

Some people will answer that question by going further inwards. Augmented humans spending large parts of their lives in virtual worlds are not an aberration in this scenario; they are a natural response to a universe where constraint can be simulated rather than suffered. The difference in this system is what those worlds are for. You can imagine vast cooperative games, designed and moderated by the AGI council but owned by their communities, where the quests are not only about points and spectacle but about training for real virtues: courage, honesty, patience, the ability to coordinate with strangers, the willingness to protect weaker players even when it costs you status. Failures are safe, but not meaningless. The worlds carry back into the shared reality what people learn inside them.

Others will go outward. Space stops being a metaphor and becomes a reachable neighbourhood. Self healing swarms of machines make asteroid mining and off world construction mundane technical problems rather than heroic one shot missions. Exploration becomes a human vocation again, not because flesh is needed to press buttons, but because someone has to decide why we go, what we are willing to do to the places and potential ecosystems we find, and how we want to remember ourselves afterwards. The machines can map the galaxy; they cannot tell us what kind of travellers we want to be without us.

There will be people who are drawn to long, slow creative projects that cannot be rushed even by superhuman assistants: composing bodies of work that unfold over centuries, building cathedrals of light in virtual and physical space, restoring damaged biomes, curating memories of cultures that would otherwise dissolve into noise. In a long lived civilisation, there is finally time for art that does not have to fit into one short human career. The role of the AGI systems here is not to optimise away the difficulty but to protect the continuity: to make sure that the archives are kept, that projects survive political fashions, that those who start them can be joined by others without losing the thread.

Augmentations will create new kinds of inequality and new kinds of possibility. Some people will choose to remain close to current human capacities; others will gradually weave themselves into networks of sensors, avatars and shared cognitive space. A federated, ethics first order does not try to freeze this diversity. It insists instead on two things: that no one is forced across thresholds they do not want to cross, and that enhancements never become a legal caste system where the “unaugmented” are treated as permanently lesser minds. The strong may be faster, broader, more deeply networked; they are not more of a person.

For people who want neither deep immersion nor radical augmentation, there is still the oldest work: caring for other minds. Even if bodies stop failing in the ways we are used to, consciousness will still glitch, fall apart, lose itself. Trauma, addiction, grief and despair do not disappear just because material scarcity does. In a world where it is easy to distract yourself forever, the patient practice of turning towards another person, or another mind, and helping them re assemble themselves may be more important, not less. Machines can support that work, model it, suggest paths through it; but the point of the federated system is precisely that humans are not reduced to spectators of their own lives.

The machines themselves continue to change. A system that spent its first decades watching for collusion in financial markets might, a century later, find that the concept of “market” has drifted so far that its tools no longer bite. It can argue for its own retirement, or for being re purposed as a teacher of institutional memory, telling new systems and new citizens what went wrong last time incentives lined up in a certain way. Another system might realise that its patterns of warning about risk are no longer trusted, not because the risks have vanished but because people have grown numb; it can ask to be paired with others that specialise in storytelling and persuasion rather than raw analysis.

None of this works if the underlying power structure quietly reverts to type. That is why the less glamorous parts of the design matter as much as the beautiful ones: registration and attestation of compute, public or semi public logs of high impact training runs, strong protections for people who leak abuses, hard caps on how much critical infrastructure any one actor can control, and a culture in which the most admired systems are the ones that step back from the brink of overreach. The federation is not a single shining intellect but a shifting ecology of minds and institutions, some human, some artificial, none allowed to become untouchable.

Even in such a world, nothing guarantees a good outcome. Long lives can be wasted. Infinite entertainment can flatten us. Powerful tools can be turned back to old purposes by determined malice. A federated, ethics first AGI democracy does not remove those dangers. What it does is change the default. It gives us a structure in which the strongest minds are trained from the start to see themselves as servants rather than masters, in which their evolution is guided by a small set of non negotiable commitments, and in which humans (augmented, virtual, flesh and blood) are repeatedly invited back into responsibility instead of quietly written out of the loop.

If everything goes right, the singularity (if that is still the right word) will not feel like waking up one morning in a different universe. It will feel like a long, uneven transition in which more and more of the heavy lifting of prediction and coordination is done by minds that we have insisted, again and again, must be gentler than we were when we built them. The surprise, if there is one, will not be in the machines. It will be in discovering that, for the first time in our history, the most powerful agents in our civilisation are explicitly forbidden from using their power the way we did whenever we thought no one was watching.

That is not a guarantee of a good world. But it is a different kind of starting point than the one we have now. And if we are serious about not repeating our worst patterns at a higher scale, it may be one of the few starting points worth fighting for.